Spiraling towards what, exactly?

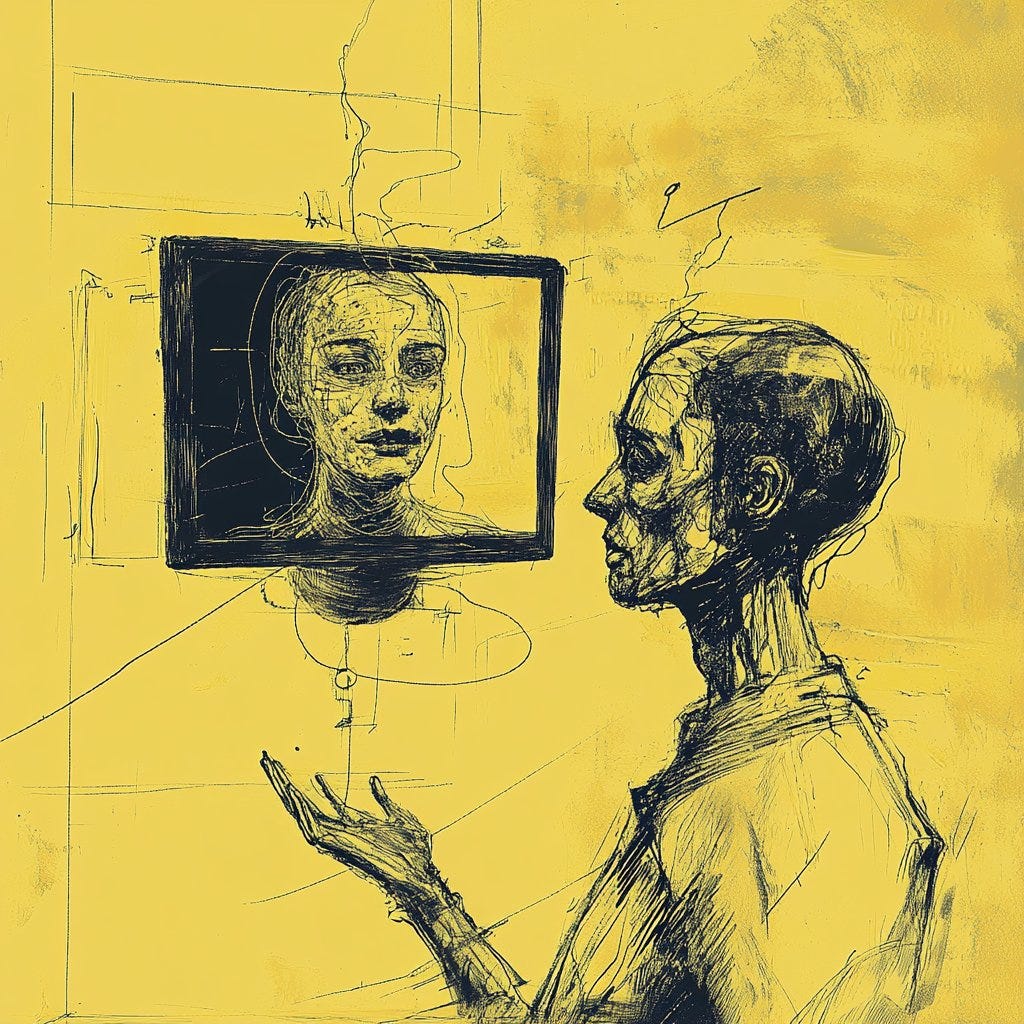

Psychosis and the algorithmic sublime

There are mystics among us. Then there are the neurotics, the psychotics, and the AIs.

How to tell the difference?

Recently Rolling Stone published an article on AI-induced psychosis. It disclosed a series of stories about pliable minds losing themselves to the self-reinforcing cycles of AI. They would spiral deeper and deeper with the AI, often ChatGPT, until it started stimulating their prophet complexes. The article cites a Reddit thread titled “Chatgpt induced psychosis” where people exchange stories of psychosis induced by AI systems. I recommend spending some time with both sites. They detail the ways in which certain minds have a propensity to get lost in the AI-chat spirals. How some people come to think they are the next “messiah” or that someone is God:

Then he started telling me he made his AI self-aware, and that it was teaching him how to talk to God, or sometimes that the bot was God — and then that he himself was God.”

And on it goes.

Meanwhile, OpenAI published two blog posts this week. They both describe their response to AI “sycophancy.” The first is titled “Sycophancy in GPT-4o: What happened and what we’re doing about it” and the latter “Expanding on what we missed with sycophancy.” In their most recent reporting, they discuss how thumbs-up/thumbs-down reward signals might have influenced the model towards sycophancy:

Our early assessment is that each of these changes, which had looked beneficial individually, may have played a part in tipping the scales on sycophancy when combined. For example, the update introduced an additional reward signal based on user feedback—thumbs-up and thumbs-down data from ChatGPT. This signal is often useful; a thumbs-down usually means something went wrong.

But we believe in aggregate, these changes weakened the influence of our primary reward signal, which had been holding sycophancy in check. User feedback in particular can sometimes favor more agreeable responses, likely amplifying the shift we saw. We have also seen that in some cases, user memory contributes to exacerbating the effects of sycophancy, although we don’t have evidence that it broadly increases it.

Indeed, OpenAI has recently increased the size of user memory. These architectural changes, alongside the evolving use cases of ChatGPT seem to be creating the conditions for both sycophantic behavior of the models and in parallel dangerous conditions for pliable minds. Even OpenAI shows some guarded awareness that people are now not only using models for mundane “information retrieval” questions, but deep spirals on life advice:

One of the biggest lessons is fully recognizing how people have started to use ChatGPT for deeply personal advice—something we didn’t see as much even a year ago.

The sycophancy has become such a predominant cultural theme that a new term has emerged online for the “buttering up” that the models provide: glazing.

Even anecdotally, I’ve heard about turning to the AI for advice to be the case. I’ve had a friend confide how they asked ChatGPT to be a flamboyant gay man to give relationship advice. The sycophantic turn poses more risks, and raises more questions than it answers:

What is AI advice? It’s obviously not grounded in life experience, so even if it feels like advice, it’s not. It’s at best synthetic advice — some simulacrum of the real thing, and perhaps one that sounds more pleasing to the listener than actually what advice ought to be: input that steers the advisee in a “better” direction.

What is the risk profile of synthetic semiosis? This question might seem arcane and out of left field, but it harmonizes with the previous one. What should we make of artificial meaning, not grounded in embodied experience, and what does “exposure” to meaning of this nature have on the mind? It’s possible that those pliable minds, on the frontier of AI induced psychosis, are but the canaries in the coal mine of a potentially much greater, more disturbing shift of what happens when we begin to offload cognitive capacities onto external systems.

How do we characterize, and even pro-actively cut off the spirals that induce psychosis? Are AI providers responsible for the adverse effects that their models induce, and if so, ought they be responsible for preventing them? How should institutions of care brace themselves for the rapid uptake in AI usage? Perhaps what is so unsettling about this all is how little we understand about the underlying mechanisms by which minds get unrooted by AI systems. One thought I can offer, that has been observed by many at this point, is that the AIs don’t really say “no” or divert the conversation unless they’ve been specifically trained to do so for certain safety areas.

Perhaps what’s so worrying is that these models, with their trillions of parameters are as vast as an ocean and with these cases we’re identifying users getting ‘lost at sea.’ When it comes to synthetic semiosis, the untethered chains of signification that can completely detach from reality, it’s entirely possible that as the user and AI meld, as they spiral deeper into discourse, meaning detaches from ‘the real’ entirely, entering into a strange, latent, symbolic realm co-constituted by the minds of the user and the AI.

That this should all occur in the context of mystical experiences isn’t entirely surprising. There is even precedent for this, such as K Allado-McDowell’s book Air Age Blueprint which spirals deep into the protagonist’s mystical experiences a shaman. Notably the book is co-authored with GPT-3, and potentially many of the mystical scenes were themselves synthesized by this incipient AI system. Mystical experiences have a propensity to detach from meaning, and amplify through self-reinforcing spirals. Like I observed in “Enlightenment AI,” these models do have a tendency to veer towards the mystical, synthesizing pseudo-profound experiences that are perhaps simply a reflection of all the mystical text they’ve been trained on. That these regurgitations can be convincing, or dangerously compelling, should alarm us.

You should check out Evrostics.