Associative tools, thinking, and creativity

On augmenting creativity

Ideas rose in crowds; I felt them collide until pairs interlocked, so to speak, making a stable combination. — Henri Poincaré

At the heart of Semioscape.org is associative thinking. Free association has been studied by psychoanalysts for over 150 years as a way of probing the unconscious, but it’s also increasingly been studied by cognitive scientists, neuroscientists, and psychologists as a way of assessing creativity and understanding the structure of memory retrieval processes. Dipping into the literature of associative thinking has brought me to the question: how can we augment human associative thought? And how can a deepened understanding of associative thinking help us create tools, metacognitive exercises, and paradigms that help people think more creatively and widely?

Creative problem solving to me often means seeing how distant and different concepts have some underlying relation, and then bringing them together in new and unintuitive ways. This could be in the context of creatively solving a math problem, building something with distant and diverse tools, or aesthetically bringing unexpected symbols and styles together. Most creative individuals I know have deep repositories of knowledge they are able to nimbly draw upon and bring to bear on the problems they’re thinking about. This might take the form of an acute memory for the domain they work in, or the ability to see how unexpected pieces “collide” and fit together. Is this kind of intuition separate from intelligence? How might we capture the essence of this kind of creative thinking in a tool like Semioscape?

To get there I want to discuss the latest science investigating the connection between associative thinking and creativity. I’ll be drawing extensively on the recent review paper: “Associative thinking at the core of creativity” published in Trends in Cognitive Sciences.1 A key area we’ll touch on is the notion of semantic space—understood through recent advances in computational modeling you may be familiar with, like GloVe and word2vec embeddings—and that I’ve also discussed in this Substack as landscapes of meaning.

We’ll find that associative thinking, particularly the ability to make distant and novel connections between concepts, is a fundamental component of creativity. This ability can be understood and quantified through the lens of semantic space. AI-augmented tools like Semioscape, which leverage these insights to support users in navigating and expanding their associative horizons, have the potential to enhance creative thinking. However, the effectiveness of such tools may depend on individual differences in associative ability, domain expertise, and attunement to the wider cultural context.

Let’s get into it.

At the core of the article is the assertion that highly creative people (such as creative professionals) are distinguished by their ability to create new connections between “seemingly unrelated concepts stored in memory.” The article cites a breath of literature to claim that creative individuals are more associative in their thinking: “they generate a broader, more idiosyncratic set of associative responses compared with less creative people.”

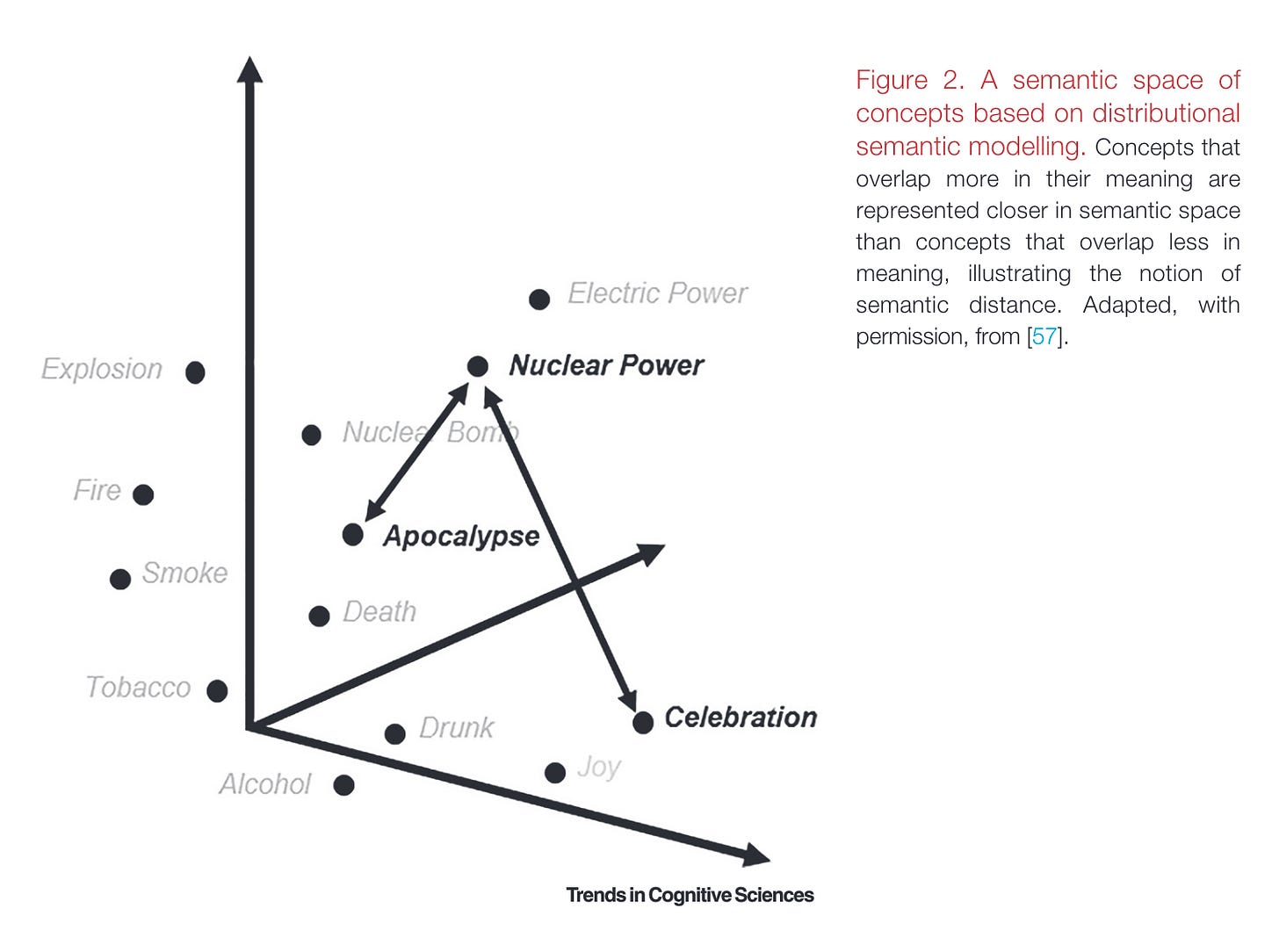

Computational models have enabled researchers to look at the quality of associative thinking with greater detail. Distributional semantic modeling, “a natural language processing modeling approach used to analyze and represent the meaning of words in a given context by studying their distribution patterns in large corpora of text,” allow researchers to quantify the extent to which concepts share semantic meaning. Embedding models, like GloVe and word2vec translate concepts into high dimensional vector representations. Semantic similarity can then be calculated by measuring the cosine angle between word vectors in high-dimensional semantic/vector space.

The notion of semantic space can be leveraged to create a variety of measures that are used to essentially measure semantic difference and similarity in associative thinking made during association tasks. One key metric is what the authors call forward flow (FF): the semantic distance between the “cue word” and all subsequently generated words, used to capture how far forward people travel in semantic space when freely associating. This will often be used in a task where a person is given a cue word—such as “candle”—and are then prompted to say the each word that comes to mind for each successive word they produce (“candle—fire, fire—burn, burn—hot, etc.”). Forward flow was then found to correlate with other indicators of creativity, such as “divergent thinking”—the ability to produce many different ideas, and real world accomplishments in actors and entrepreneurs.

The authors point out that FF was predictive of divergent thinking when controlling for intelligence, even on a wide battery of intelligence tests—indicating that free association is “psychometrically distinct” from intelligence. Free association might tap into other forms of intelligence, like verbal fluency (efficiently retrieving words from memory) and crystallized intelligence (knowing many words’ meanings). In other words, semantic ability could perhaps be seen as its own kind of intelligence. Is it one that can be augmented, perhaps irregardless of wider expertise or intelligence?

Aside from FF, the authors point out other metrics that were used to capture “retrieval dynamics predictive of creative thinking”—i.e. semantic ability. One is clustering—the number of categories visited, another is switching—alternating between semantic categories, complexity—the range of combinations of different semantic categories, and other distance metrics like global semantic distance (FF) and local semantic distance—distance from previous response. As they show in Figure 4, high creative participants traveled further in the network, switched between more subcategories, and made larger leaps between their associations.

In building a tool that augments associative thinking, we might think of Semioscape as a kind of “cognitive prosthetic” for traveling through semantic space. Semioscape allows users to travel in semantic space by showing them associations to a given node, and then letting them select and create yet further associations. By AI-generating associations, we present the user with associations that they might not have thought of, and that allows them to travel further, faster through semantic space. In addition, we can adopt some of the distance metrics elaborated on in this article, like forward flow (FF), to illustrate to the user which points in the associative network are more semantically similar or distant.

Of course to truly establish whether Semioscape is augmenting a user’s semantic reach will require detailed empirical testing. This might be pursued in creating variations of the association tasks highlighted in the article where the participant first free associates words without the tool and then does it using the tool’s augmentation. We could apply the same evaluative metrics to the associative graphs created in the tool to understand how different users are traveling through semantic space: switching between semantic categories, the complexity of the graphs they create, and the semantic distance they traveled.

More broadly, we can think of how tools like Semioscape have the potential to augment human creativity. To do so might require having a more refined understanding of associative thought in creativity. Here, I revisit Mednick’s seminal paper “The Associative Basis of the Creative Process” (1962).2 In Mednick’s associative definition of creativity, he identifies three ways creative solutions might be achieved: serendipity, similarity, and mediation. Mednick starts by giving an associative definition of creativity: “the creative thinking process as the forming of associative elements into new combinations which either meet specified requirements or are in some way useful. The more mutually remote the elements of the new combination, the more creative the process or solution.” In highlighting three ways of achieving a creative solution, Mednick breaks down the processes of associative thinking that might bring about a creative outcome:

Serendipity — “The requisite associative elements may be evoked contiguously by the contiguous environmental appearance (usually an accidental contiguity) of stimuli which elicit these associative elements.” Here he cites the discovery of the X-ray and penicillin.

Similarity — “The requisite associative elements may be evoked in contiguity as a result of the similarity of the associative elements or the similarity of the stimuli eliciting these associative elements.” Here he cites creative writing, that leverages “homonymity, rhyme, and similarities in the structure and rhythm of words or similarities in the objects which they designate.” He speculates that “It seems possible that this means of bringing about contiguity of associational elements may be of considerable importance in those domains of creative effort which are less directly dependent on the manipulation of symbols.” Such as painting, sculpture, musical composition, and poetry. What’s interesting is in Beaty and Kenett, they observe that in association tasks given to award-winning visual artists and research scientists, the artists overall produced significantly more semantic distant associations. They note that although the association task was verbal, the artists were trained in the visual domain so their performance could not be explained by advanced verbal abilities.

Mediation — “The requisite associative elements may be evoked in contiguity through the mediation of common elements. This means of bringing the associative elements into contiguity with each other is of great importance in those areas of endeavor where the use of symbols (verbal, mathematical, chemical, etc. . . .) is mandatory.” This might be seen as a facility to do goal-directed association through semantic space, curating select associations in order to reach a goal state or to identify isomorphisms between associations. In Beaty and Kenett, they distinguish goal-directed association (“strategically combining concepts”) from free association (“spontaneously connecting concepts”).

Semioscape relies on all three properties in how it enhances creativity. It creates the conditions for serendipity by creating unexpected AI-generated associations. It simultaneously has the property of similarity, by exploring local regions of semantic space to the cue word that’s given by the user. It allows users to explore the property of mediation by making common elements visible even in the midst of drastically different input concepts.

This could help with goal-oriented association tasks, where users might, for example, be doing a futuring/scenario-planning task where they explore positive and negative counterfactuals and want to ascertain what kinds of counterfactual outcomes are common to a variety of disasters. By creating parallel associative chains, isomorphisms and differences become visible and common associations are also rendered to the user.

But is creativity merely a case of semantic ability—the facility with navigating semantic space via free and goal-directed associations? It seems one key factor that’s not elaborated on by the literature is the ability to situate associations against a wider cultural context. This might be a kind of “associational integration” where a creative individual is able to identify the wider semantic space that they’re working in—associations that link up to a cultural zeitgeist or umwelt—where certain signs or symbols carry cultural weight. For example, the watermelon has become a symbol for a free Palestine and thus its integration into a work of art might link up to the kinds of associations that exist in the wider cultural sphere that are connected with Palestinian liberation. Art historians and theorists are particularly attuned to these kinds of recurring motifs in the arts/online/cultural sphere—for example, in Alex Quicho’s “Everyone Is a Girl Online”3 describes the girl as a symbolic-consumer-inhuman category, perhaps accelerating towards becoming the Total Girl:

It may well work in our favor to accelerate our way into Total Girl—that is, to consider the girl as a specific technology of subjectivity that maxes out on desire, attraction, replication, and cunning to achieve specific ends—and to use such technology to access something once unknowable about ourselves rather than for simple capital gains, blowing a kiss at individually-scaled pleasures while really giving voice to the egregore, the totality of not just information, but experience, affect, emotion.

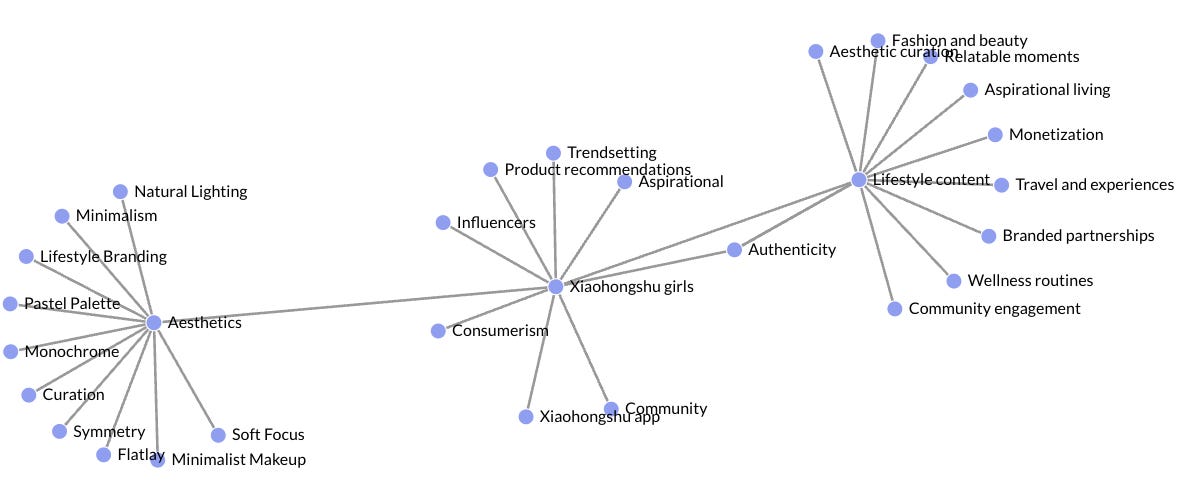

In her article, Quicho surveys what it means to be a girl in the complex semiotics of the online landscape, spanning from consumer-informed notions of femininity to how Xiaohongshu girls are acting as a “unidirectional source of inspiration” on Anglosphere platforms. This kind of associational creativity requires more than just associational ability, but an attunement to the wile and varied semiotic landscape of being online.

For now, this might be a domain where Semioscape falls short. Its models are not up to date with the latest niche trends and memetic landscape. Indeed, the model’s training stops at August 2023. It won’t pick up on the latest associations with couches. And while it can give associations with Xiaohongshu girls, they are vague and “washed out,” far from sufficient to give an aesthetic account that could be replicated. To augment this kind of tapped-in associational creativity will require models that are as online as we are, probing the latest trends and memes for associational signal. While the model might do this well on historically well-established semiotics, in its current state it can hardly keep up with the accelerating cultural flux that characterizes online platforms.

In my own experiences of using Semioscape to augment my creativity, I will start by resetting the tool and then thinking about the task I want to take on. I find that thinking about how I want to think primes me for working in this more associative way. For example, I was intrigued to explore the conceptual landscape around Xiaohongshu girls, as it was an unfamiliar concept to me. So I entered it into the tool, and then did a critical evaluation of the associations it returned. I noticed some resonances with the aesthetics of Tumblr girls. And noticed there was the commonality of “Pastel Colors” for Tumblr girls and “Pastel Palette” for Xiaohongshu girls. Expanding on this node then created further common links between the two girl aesthetics. I can then further expand nodes to explore the connotations of pastel colors, and so on follow my curiosity by intentionally expanding nodes I know little about and thereby fortifying my own mental lexicon of associations.

Another way of using Semioscape is to map out my own semantic memory by systematically entering a diverse array of concepts I know about, and then looking for unexpected connections and patterns. I might start by prompting myself to think about what books I’ve read and concepts I’ve encountered, entering each into the tool and expanding their associations. Although the associations might not perfectly fit with how I’ve thought about a concept—for example, for “noosphere” it might associate “spirituality,” a dimension of the concept I’ve not thought much about—this can be positive, as it expands my own understanding of concepts I already know, showing alternative associations that might reveal gaps in my knowledge. Doing this at length—entering in lots of concepts I’m familiar with—also gives me a kind of “mind map” where ideas collide and coalesce in emergent ways. This is fertile ground for novel insights, as much in the connections I see the tool make as in the ones that are absent, but that I think should be there. In both cases, the insights are fruitful. Indeed, if you have 15 minutes, I’d recommend giving it a try.

Much like participants in associative thinking experiments are told to free associate or do a goal-directed association task, priming users with how to think might turn out to be an important feature of the tool. To this end, I’ve begun experimenting with a series of “metacognitive prompts” (metacognition is thinking about thinking). These prompts are different instructions for how to reflect on your own thinking when using the tool, tailored to the kind of task that the user wants to undertake. This could be using the tool as a “Design Aide” or for “Futures Thinking and Scenario Planning.” These prompts are still under development, but soon you’ll see them appear in the tool.

Semioscape aims to mirror the structure of associative thought. Letting disparate ideas collide and give way to new forms. In this Substack, we’ve looked at the latest research in associative thinking and creativity to better understand how to measure correlates with divergent thinking and looked to Mednick’s foundational work to see how serendipity, similarity, and mediation might themselves be design elements in Semioscape that fortifies its ability to be a cognitive prosthetic for creative thinking. We’ve seen how the concept of semantic space can be useful for understanding creativity—particularly how creative individuals seem to switch categories, and create more complex associative networks. Does this suggest that creative individuals might get more mileage out of a tool like Semioscape? Or that its built-in serendipity might help anyone travel further, faster through semantic space? And how might those deft with “associational integration” with the wider cultural sphere make use of this tool, in spite of it being locked in time?

Beaty, Roger E., and Yoed N. Kenett. 2023. ‘Associative Thinking at the Core of Creativity’. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 27 (7): 671–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2023.04.004.

Mednick, Sarnoff. 1962. ‘The Associative Basis of the Creative Process.’ Psychological Review 69 (3): 220–32. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0048850.

https://www.wired.com/story/girls-online-culture/