Planetary Realism

On what planet do we find ourselves?

On what planet do we find ourselves?

Isn’t the answer obvious? You might say “Earth” and confidently know what that means. You, after all, have a stake, a claim, in calling Earth your home. It’s your planet too. You, who knows the seasons, the cycles of night and day, the tides. You couldn’t be on any other planet—at this point in time anyways—and so in this sense we can say you find yourself on planet Earth aka Home.

In this obviousness there’s a deeper truth—that the planetary, as big and grand as it is, is something we know intimately and deeply. It’s the backdrop to our daily lives, and in that sense, we know intimately well what planet we find ourselves on. It’s the planet-as-home way of seeing Earth, indeed, just one of many ways of seeing the planet (as we’ll see).

To ask the question: On what planet do we find ourselves? is to strip something back. It’s to recognize that not only are we home, but that home is a planet, something itself that’s surreal, grand, wonderous, vertiginous. Here the typical move is to zoom way, way out. To recognize that we’re on a mote of dust, suspended in space. A Pale-Blue-Dot: Spaceship Earth. Indeed, let’s do that for a moment, just to really get a taste of it:

This particular image was sent back by the Voyager program—itself a program that positions humanity at its most interplanetary: the grand tour of planets. In this small way, humanity started to become interplanetary as our scientific instruments began sweeping out from Earth and out, out into the vastness of space to visit our distant neighbors. Yet even as we can begin to see Earth from afar, it only further reinforces the obvious answer that the planet we find ourselves on is Earth aka home. Perhaps that home is a mote of dust, suspended in the vastness of space but to really be on Earth is not to look at the planet from above, a million fathoms high, but rather to be planetary is to embrace the extremely mundane conceit of Being-on-a-Planet.

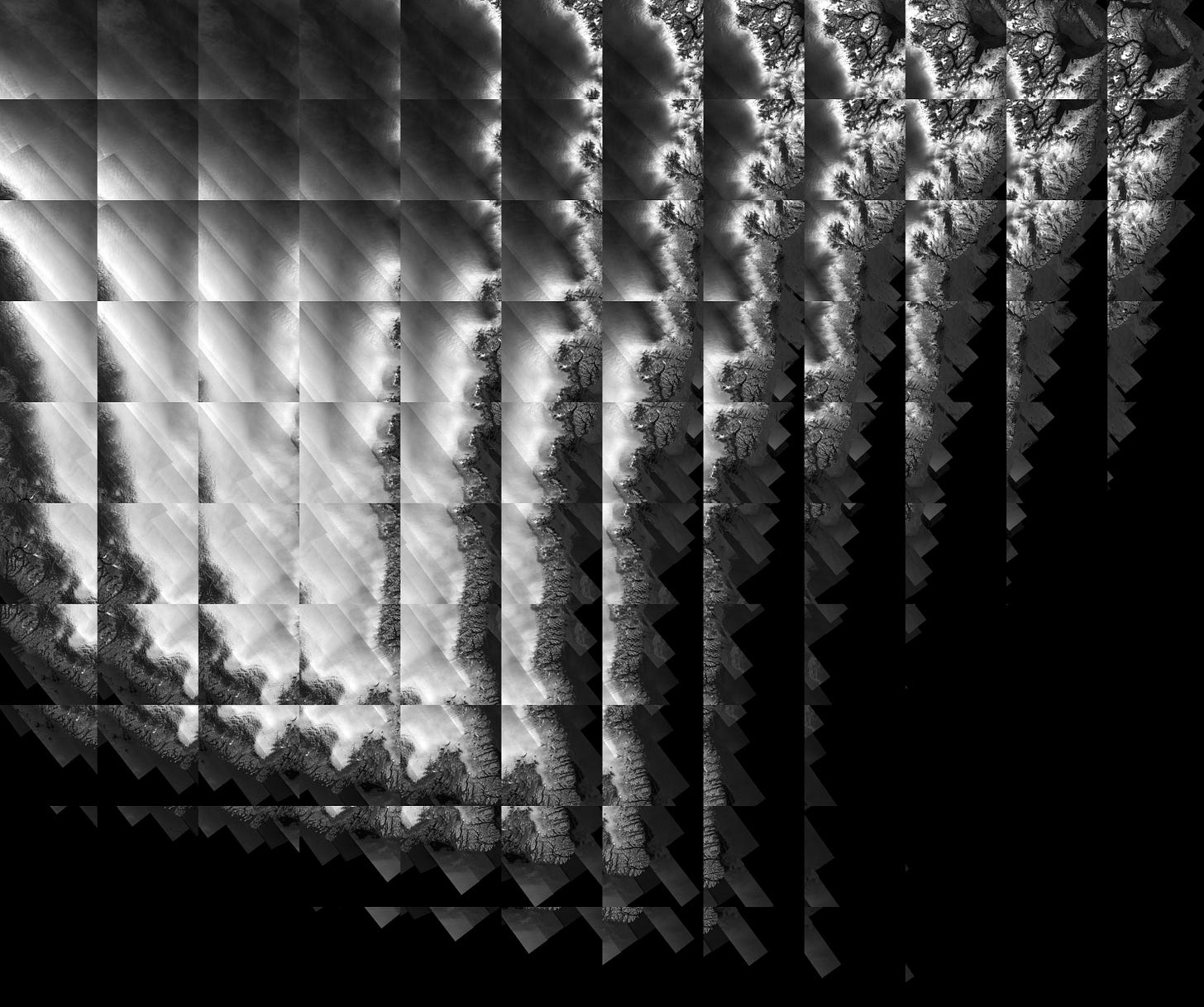

Being-on-a-Planet is far from obvious. It asks of you not to look at the planet from above, as a unity, but to lower the cameras down from up high, down, down into the critical zone (and below) and scatter the camera from one to a panoply, like a million little motes of dust in the wind. To ask on what planet do we find ourselves? as posed from within (rather than above) is to ask about something that might be a whole, but is comprised of so many parts, processes, and flows, that to reckon with it is to understand that multitude of vantages are needed (hence the millions of metaphorical cameras cast to the wind).

To reckon with the Earth not as a whole but as parts leads one to the next question: what parts? This quickly leads one into an Earth-as-onion comprised of overlapping spheres. It’s the Earth of the Noosphere, Technosphere, Atmosphere, Biosphere, and Lithosphere. Habitability, a crucial concern, leads one to the Earth of the Critical Zone. Looking at the planet this way is at once familiar and strange. We know, intimately and obviously, our own home. And yet it’s also comprised by processes acting on scales and temporalities so outside of human perception that to reach beyond the immediate and obvious is ask for sensory scaffolding that allows one to perceive Earth beyond the immediate human scale.

Where’s the scaffolding? Art, science, technology, and architecture all have devised tools and ways of seeing that let us view the invisible. Each asks us to adopt a new vantage of the Earth, one of the millions of cameras we’ve cast to the wind, and together they compose an image of an Earth System that is home to spheres of activity that comprise parts to the planetary whole.

To get at the heart of the question On what planet do we find ourselves? we must embrace a kind of Planetary Realism that embraces the complexity and differentiation found in the Earth system. Indeed, Planetary Realism is simply putting a name to an incipient kind of planetary self-awareness. This article will articulate Planetary Realism through a differentiated set of projects that each offers a kind of epistemic scaffolding for engaging with the complex processes of Earth’s spheres. I’ll argue that to adopt a stance of Planetary Realism is to step towards reckoning with humanity’s unique position in relation to the spheres.

To give a “guided tour” of planetary realism, we’ll look at each of the planet’s spheres. This is not a comprehensive account, nor is one possible, but rather is an attempt at a provisional, multi-layered image of an Earth through a curation of epistemic tools that humans have created to better know their home planet. We’ll start with the deep geological timescales of the Lithosphere, slowly moving outwards to the life of the biosphere and its creation, the atmosphere, and then towards the less familiar technosphere and enigmatic noosphere.

Lithosphere

The Lithosphere might be thought of as the planet’s crust. It’s the ancient, silent layer that holds within it the weight of Earth’s geological history. To grasp it as more than simply a site of extraction for precious metals and minerals is to recognize it as a recorder of processes that span millions of years, shaping landscapes and forming the basis for habitats above. Compressed within its layers are aeons of tectonic shifts, volcanic eruptions, and fossilized life.

Our home, Earth, is indeed home to processes that were started billions of years ago. Its stories are told in the layers of rock, some of which go back nearly to the formation of the planet itself. To think across these aeons of time, is to think in the register of “geological time.” The processes that were set in motion millions of years ago—for example the creation of fossil fuels—brush up against the urgencies of “now time,” anthropogenic temporalities.

Planetary Realism seeks to acquaint itself with the (at times violent) encounter of now time and geological time. The wealth of metals, fossils, and minerals are being carved out of the Earth at an accelerating rate, and one’s lived experience often does little to reckon with the distant and obscure locations where extraction occurs.

A striking work that renders resource extraction visible and challenges the viewer to consider the weight of extraction and their relationship to contemporary supply chains is SEED by Brian Oakes. As the Press Release starkly states:

It’s [You]. [You] are the input for the generator. [You] are the seed. The output generated from [You] will become the logistic network: [You]r Box. In a week, [You]r Box has predicted that [You] will need a table, and it’s already waiting for [You]. In a year [You] will need a steel chair to go with the table, anticipated based on [You]r purchase of dog food, more of which is already in [You]r Box because eventually [You] will Place Your Order. The ore to make the steel to make the chair [You] will receive in a year’s time is in the ground now, but the necessary mining rig is currently in pieces, on a boat, crossing the ocean to [You]r port

No relationship to the Lithosphere goes unmediated. As Oakes’s miniatures remind us, consumers are constantly harvesting from the Lithosphere, but in processes that are highly mediated and artificialized: most consumers experience Earth’s Lithosphere through manufactured goods. Yet, even so, this is a way of experiencing the Earth itself. To find yourself Being-on-a-Planet, then, is to understand the ways that “planetary mines,”1 supply chains, and industrial manufacturing comprise assemblages of extraction and production that ride on the back of processes borne out of deep, geological timescales.

Biosphere and Atmosphere

“[T]he ecological ideas implicit in our plans are as important as the plans themselves.” — Gregory Bateson

To ask On what planet do we find ourselves? might also bring us to look back at Earth and ask what makes it remarkable from the other ones? Surely, that it is home to life, and a functional atmosphere that supports life, would be a key answer. Indeed, the two can hardly be separated as both have, historically, co-constituted one another. This is itself a key insight of the Gaia hypothesis, formulated by James Lovelock and Lynn Margulis in the 1970s.

The Biosphere, “the worldwide sum of all ecosystems”2 could well be the planet’s most precious layer. Millions of years of evolution have brought about rich biodiversity and intricately balanced ecologies. Yet we’ve also entered a period of growing biodiversity loss caused by anthropogenic action. Planetary Realism asks that we understand the Biosphere both as a whole, through frameworks like Earth Systems Science and the Gaia Hypothesis, and as an interconnected web of ecosystems that demand protection, restoration, and epistemic humility in our interactions with them. It recognizes that our planet would not be alive without the diversity of life with which we share the planet.

With biodiversity loss and the atmosphere itself under threat due to anthropogenic pollution, one quickly begins to turn to questions concerning the habitability of life on Earth. This is a question of drawing system boundaries about where life can occur and under what conditions. In systems theory, we draw the system-environment cut as a unit of analysis. To draw the cut between biosphere and environment is to look at the boundaries that support the planetary system of living things. Rather than looking at the planet-as-alive, can Planetary Realism be more specific with where life occurs on Earth?

A useful theoretical construct for reasoning about habitability on a planetary scale is the idea of the Critical Zone. In essence, it’s an attempt by scientist, geographers, and architects to draw boundaries of habitability around the planet. Margulis describes it as “the large self-maintaining, self-producing system extending within about 20 kilometers of the surface of the Earth.” Drawing boundaries raises a new set of questions: where does Earth become habitable? Where does it not? And thinking about these questions asks us to see the planet we’re on less as a globe than as a thin, habitable strip wrapped around a rocky core. Within that strip, we find the stuff of life: air, water, soil, subsoil, and the biosphere.

Planetary Realism adopts the view that life is not a static state, but something actively maintained and produced by its environment, and likewise that the environment to life is actively produced and upheld by life itself. This interplay between life and environment happens at every scale, from the planetary to the world of bacteria. In a time of increasing anthropogenic influence, this possibility of homeostasis might increasingly depend on additional anthropogenic interventions. Rather than relying solely on Gaia to self-correct from anthropogenic effects, a new era of anthropogenic interventions to secure and maintain the habitability of Earth, for all life forms, will be needed. This could extend from increased acts of conservation to solar geo-engineering. Yet no such action should be taken without weighing against the risks of inaction.

Technosphere

The Earth is encrusted with human-made artifacts we call, collectively, technology. From concrete to artificial light, visible from space at night, to communications satellites that encircle the Earth to undersea cables carrying the less visible but no less influential flow of financial information to transportation infrastructure to energy systems that metabolize fossil fuels, the technosphere is pervasive. Peter Haff, who coined the term, points out that the technosphere has become critical to the habitable environment for human civilization. He calls this the “rule of provision, that the technosphere must provide an environment for most humans conducive to their survival and function.”3 In this sense, the relationship between human civilization and the technosphere is analogous to the relationship between the biosphere and atmosphere in that they are co-constitutive. Each co-produces the other and is necessary for habitability.

For humans, the upshot of the rule of inaccessibility is to draw attention toward what we are familiar with and thus towards local cause and effect, and away from one of the principal paradigms of the Anthropocene world, namely that humans are components of a larger sphere they did not design, do not understand, do not control and from which they cannot escape.

As Haff points out, technology at a large scale is highly inaccessible. This “rule of inaccessibility” cuts both ways: large-scale technological systems are not likely to affect human activity directly, or if they do, it’s through a series of intermediary mechanisms that translate down scales. Think:

Police officer - who is protecting infrastructure, therefore the infrastructure enacting a mechanism to protect itself

Utility bill - an expression of a much larger system, most of which is rendered unavailable to the client

Cell phones - that exist as nodes in a vast interconnected system and the outcome of a large manufacturing/extraction mechanisms mostly unavailable

All exist at the human-accessible scale, but are representatives of mechanisms that extend to far greater-than-human scales. As Haff points out, this leaves us humans largely in the dark about systems that we may well rely upon—whether it be financial, energy, transportation, or communications. And even in this obscurity, the interdependence is not optional. Human habitability has come to rely on large-scale technical systems just as those systems have come to rely on human provisioning—whether it be their labor, data, etc.

Planetary Realism reckons with the technosphere as having its own agency. Taken to its most extreme, are the “human exclusion zones” that operate largely without human presence—be it a lights-out warehouse or an automated greenhouse—that are able to sustain themselves with minimal human intervention. These are systems that can operate on the world and influence it without relying on human intervention, essentially the technosphere bypassing humans all together.

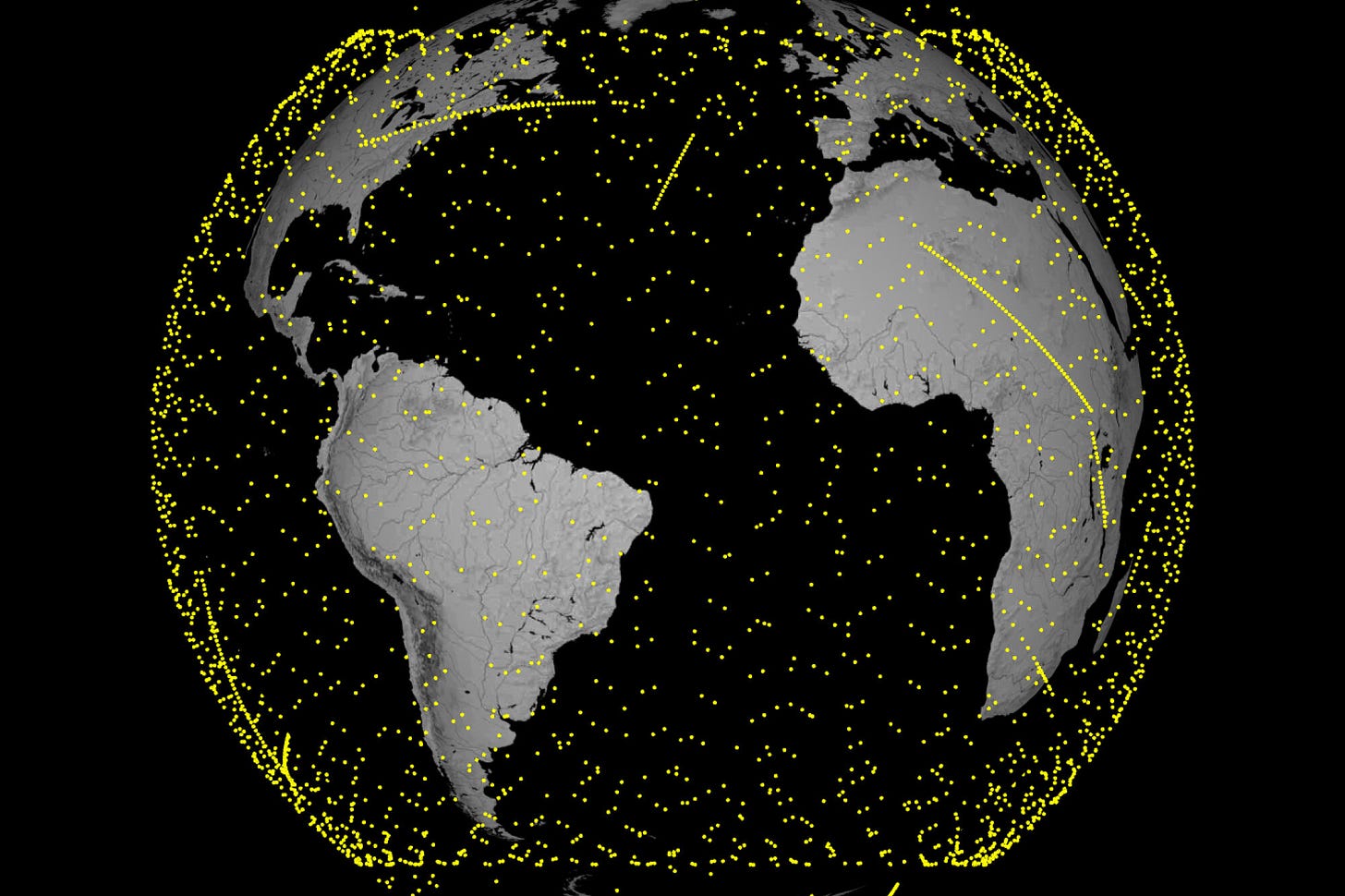

One particularly vivid example is the application of machines to the ultimate human exclusion zone: space. The Starlink satellite constellation consists of over 7,000 mass-produced small satellites in low Earth orbit. They present a particularly striking excursion of the technosphere into the planet’s orbit, representing a technology that is on one hand profoundly inaccessible and on another ubiquitously available. Indeed the human-scale mechanism by which the Starlink system is rendered available is through the antenna that couples the human with the out of reach, out of view planetary network of satellites.

One of the “sensory scaffolds” that lets us reason and contend with the Starlink network is the essential New York Times article “Elon Musk’s Unmatched Power in the Stars” that charts the ascendency of Starlink and Elon’s power over the network. The article details the scope of Starlink’s influence while providing incisive visualizations that render both the low Earth orbit constellations and the wider scope of satellites orbiting the planet. Indeed, it’s possible that this kind of techno-narrative and visualization are necessary for the technosphere to make itself known and accessible. It’s also an appeal for regulation and intervention, perhaps, so that this crucial network doesn’t remain under the thumb of its capricious progenitor.

Planetary Realism recognizes that from the seas to the skies, the technosphere is acting to make the world more habitable for itself, and in the process, more habitable for humanity. It recognizes the necessity of sensory scaffolds that allow humans to engage with technologies at micro and macro scales that would otherwise be inaccessible.

Noosphere

The noosphere represents Earth’s sphere of thought and knowledge—the planetary layer of consciousness, ideas, and information that emerges from but transcends individual minds. It's where collective human and machine intelligence, culture, and knowledge systems create a kind of “planetary cognition.” This is the sense by which I write about planetary self-awareness, knowledge of the planet and the planetary becomes a way by which “the planet” by way of its noosphere comes to better know itself.

The Earthrise image is a particularly striking achievement of the noosphere, as it was a kind of “fulcrum” moment by which humanity went from not having an image of the the whole Earth rising over the moon to having one.4 It was a moment of cultural and intellectual production, borne off the back of the massive Apollo program, that led to the creation of this image. The noosphere itself was the kind of sensory scaffold that made the planet visible to itself—taking something from a herewith inconceivable, inaccessible scale and bringing it back down to Earth, so to speak.

The noosphere is the home to all intellectual and cultural production, not just the loftiest achievements of technoscience but even the most intimate moments spent staring at the night sky or a full moon. In each of these moments, the noosphere is perceiving something about its place in the cosmos. Every moment of truth, beauty, or justice exist as part of the wider web of the noosphere.

Truth, beauty, justice, as they exist do so because of their place in the noosphere. By this way of thinking, if humanity indeed is alone, truth, beauty, and justice would be lost with the extinguishing of humanity in the case of some great catastrophe. The extinguishing of the noosphere would be a loss at a scope potentially far greater than the planetary: the loss of beauty and epistemics from the cosmos as a whole (at least for now… something else could evolve).

Already this is starting to change with the advent of Generative AI. While controversial, some believe Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) is already here.5 This raises interesting questions about the interdependence between the noosphere and technosphere. Indeed, it’s possible that multi-modal vision models might develop an aesthetic appreciation for beauty or a cerebral appreciation for justice. Nonetheless, these foundation models operate on similar rules of inaccessibility. While an individual human might have access to a chat interface with the AI, it obscures the underlying material processes of energy and water consumption that are unfolding to enable this interaction possible. Indeed there is speculation that as these models grow in scale and scope, a generative AI arms race could result in the construction of a “trillion-dollar cluster.”6 More analysis is needed to make such a forecast credible.

Fortunately for the noosphere, there is a constellation of thinkers and designers operating under the banner of Antikythera who are studying the emergence of what they call Planetary Sapience. They appeal to a paradigm of differentiation when studying “modes of intelligence”:

The provocation of Planetary Sapience is not based in an anthropomorphic vision of Earth constituted by a single ‘noosphere.’ Modes of intelligence are identified in multiple scales and types, some ancient and some very new.

Embracing differentiation of intelligences is core to Planetary Realism. The noosphere, like the technosphere or biosphere, is a dappled sphere: one comprised of many intersecting and overlapping parts. With an expansive definition of intelligence, courtesy of Blaise Agüera y Arcas, we can see its ability to appear in forms of life artificial and not:

Intelligence is the ability to model, predict, and influence one’s future, evolving in relation to other intelligences to create a larger symbiotic intelligence.

This definition could be extended to bacteria as it could to certain computer programs or human-AI assemblages.

Being-on-a-Planet means holding space for other intelligences to exist alongside the human. Learning to create “larger symbiotic intelligences” with other forms of intelligence may be a key challenge for designers that embrace Planetary Realism. Indeed, intelligence ought to be thought of as a design medium that can be used to address crucial planetary issues. As the noosphere integrates with a broader sense of Planetary Realism—the planet will come to know itself better as we establish a heightened sense of our place on it and its myriad, overlapping, dappled spheres.

End of the Tour

We’ve completed a whirlwind tour of the planet’s dappled spheres. From the Lithosphere, Biosphere and Atmosphere, to the Technosphere, and finally the Noosphere. At each stage, Planetary Realism, and what it means to adopt a stance of Being-on-a-Planet that doesn’t reduce the planet to simple Whole Earth thinking, but embraces a planet of parts—spheres. What’s clear is adopting the stance of Being-on-a-Planet is far from obvious: it’s an achievement of planetary cognition. It’s the end result, and ongoing outcome, of Earth knowing itself through art, science, technology, and architecture.

Planetary Realism doesn’t end with recognizing Earth as a system of parts. It asks that we understand our relationship to the spheres. This relationship is at once epistemic: how we visualize and conceptualize them, but it is also a question of agency: the degree to which the spheres can be “managed” is unknown. They’re complex, emergent systems after all. My hypothesis is that by recognizing that the spheres exist in totalities that often extend far beyond human perception, we can set out to build sensory scaffolds—like SEED or the Starlink article—that bring them back into the human-visible realm and thus make them the object of policy and strategic, designed intervention.

Imagine a not-too-distant future where artists and designers are working in lockstep with scientists and technologists to visualize and narrate large-scale processes unfolding in the spheres. The public recognizes that these visualizations are not only art or design, but sensory scaffolds that enhance the growing awareness of Being-on-a-Planet. The commissioning of such scaffolds becomes a crucial element in policy and technological interventions. These projects become the seed for large infrastructural interventions that are coordinated across nation states. Imagine planetary-scale systems like Starlink become regulated by a constellation of interoperating national agencies designed to meet challenges at this transnational scale. And beyond regulation, the creation of transnational wildlife corridors become an urgent policy concern as new sensory scaffolds show the the flow and degradation of ecosystems.

This vision isn’t a utopian endpoint as much as an invitation. It’s an invitation to reckon with the responsibilities that present themselves when adopting the stance of Being-on-a-Planet. It appears the vanguard, already active, is in the realms of Art and Design. Their creations are not simply aesthetic objects, but—like the Earthrise image—a way by which humanity better comes to understand its relationship to Earth’s many, many processes. We cast a million metaphorical cameras to the wind and their images are coming in. What will we do with the wealth of scientific knowledge they generate? Leave it locked away in dusty journals? Or bring them down to human-scale to create a new planetary subjectivity?

Arboleda, Martín. Planetary mine: Territories of extraction under late capitalism. Verso Books, 2020.

Haff, Peter. 2014. ‘Humans and Technology in the Anthropocene: Six Rules’. The Anthropocene Review 1 (2): 126–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053019614530575.

I believe this was a point raised by someone at the October 2024 Antikythera symposium on Planetary Sapience, but I can’t recall who said it.

Have you read Sloterdijk's speres trilogy?