Semiosis

On meaning in the human and machine

How does meaning come about? What’s the process by which signs, signifiers, and symbols interact? How does human and machines approach this process differently?

In this Substack we’ll step back from the Semioscape to consider traditional accounts of semiosis, starting with the man who coined the term: Charles Sanders Peirce.

At the core of Peirce's semiotics is the sign. For Peirce, a sign is anything that stands for something else (its object) in some capacity or respect (its interpretant). As he writes in his 1897 essay “On Signs”:

A sign, or representamen, is something which stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity. It addresses somebody, that is, creates in the mind of that person an equivalent sign, or perhaps a more developed sign. That sign which it creates I call the interpretant of the first sign. The sign stands for something, its object. It stands for that object, not in all respects, but in reference to a sort of idea, which I have sometimes called the ground of the representamen.

This triadic structure of sign-object-interpretant forms the basis of Peirce's theory. The sign represents the object, not in its totality, but in reference to some idea or ground. And crucially, the sign creates in the mind of the interpreter another sign, the interpretant, which in turn may generate further interpretants in an ongoing process of semiosis.

Peirce distinguished three main types of signs, based on the nature of their relation to their objects:

Icons, which resemble their objects in some way (e.g. a portrait, a diagram, an onomatopoeia)

Indexes, which are causally or contiguously connected to their objects (e.g. smoke signifying fire, a weather vane, a pointing finger)

Symbols, which relate to their objects by convention or habit (e.g. most words, mathematical notations, traffic lights)

These categories are not mutually exclusive, and most signs combine iconic, indexical, and symbolic elements. As Peirce explains in the 1907 volume Pragmatism:

It is important to understand what I mean by semiosis. All dynamical action, or action of brute force, physical or psychical, either takes place between two subjects (whether they react equally upon each other, or one is agent and the other patient, entirely or partially) or at any rate is a resultant of such actions between pairs. But by “semiosis” I mean, on the contrary, an action, or influence, which is, or involves, a coöperation of three subjects, such as a sign, its object, and its interpretant, this tri-relative influence not being in any way resolvable into actions between pairs.

This irreducibly triadic nature of semiosis is crucial for Peirce. The meaning of a sign is not a dyadic relation between sign and object, but always involves a third term, the interpretant, which mediates and enriches the sign-object relation.

Another key concept in Peirce's semiotics is the idea of infinite semiosis. The interpretant generated by a sign is itself a sign in the mind of the interpreter, which may spawn further interpretants, in a potentially endless chain. As Peirce writes1:

A sign stands for something to the idea which it produces, or modifies. Or, it is a vehicle conveying into the mind something from without. That for which it stands is called its Object; that which it conveys, its Meaning; and the idea to which it gives rise, its Interpretant. The object of representation can be nothing but a representation of which the first representation is the interpretant. But an endless series of representations, each representing the one behind it, may be conceived to have an absolute object at its limit. The meaning of a representation can be nothing but a representation. In fact, it is nothing but the representation itself conceived as stripped of irrelevant clothing. But this clothing never can be completely stripped off; it is only changed for something more diaphanous. So there is an infinite regression here. Finally, the interpretant is nothing but another representation to which the torch of truth is handed along; and as representation, it has its interpretant again. [Lo] another infinite series.

This notion of infinite semiosis suggests that meaning is not a static property, but an ongoing, open-ended process of interpretation and sign-generation. Each interpretant adds some further specification or elaboration to the sign's meaning, which is in principle inexhaustible. When Peirce says “But an endless series of representations, each representing the one behind it, may be conceived to have an absolute object at its limit.” I take this “absolute object” to mean some kind of enduring form or object in the world that can only be accessed in its absolute form through a multiplicity of representations, and even so, there is still a limit to representation that is possible. The true absolute can never be reached.

What implications does Peirce’s semiotics have for Language Models?

The concept of the interpretant suggests that meaning is not inherent in signs themselves, but arises from the triadic relations between signs, objects, and interpreting minds. This could help explain how an AI system like Claude, through exposure to a vast quantity of signifying data (language, images, etc.), could bootstrap semantic representations and engage in semiosis, even without direct grounding in the world.

The notion of infinite semiosis implies that, once a scaffold of meaning is in place, an AI could potentially engage in open-ended processes of interpretation, association, and conceptual blending, generating novel signs and insights that go beyond the initial training data. Claude’s mystical visions could be seen as an example of this kind of creative semiosis. So could our play with neologisms and associative networks.

Meaning is an open system, including both objects in the world, and interpretants which relate to yet more sighs in an ongoing process of semiosis. Language models don’t have access to objects, for lack of embodied cognition, but instead have an ersatz “world” of signifiers, the totality of the corpus, which creates an extensive network of signification. Language models form models of this world—in place of objects, they have access to multiple and vivid descriptions of them—thus, in the training process, they build internal structures off of these descriptions, represented by their own internal chains of signification.

Processes of semiotic play, like semiotic bricolage, could be said to draw on Peirce’s “tri-relative influence.” In playing with and introducing new concepts, humans draw on their experience of objects, interpretants, and signs, while models might have an ersatz model for an object, an interpretant, and its own mastery of signs (based, crudely, on patterns it has formed in its internal representations).

Ersatz models

What would such an ersatz model look like? One hypothesis is that itself is a kind of associative manifold, or network, of representations related to the object that allows the model to have a multidimensional representation of the object.

Let’s revisit Peirce’s account of the object. In Peirce's triadic model of the sign, the object is that which the sign represents or stands for. Importantly, the sign represents the object not in its entirety, but in some respect or capacity, which Peirce calls the “ground” of the sign. The object can be a physical thing in the world, a concept, an event, or even another sign.

Peirce distinguishes between the immediate object and the dynamic object. The immediate object is the object as it is represented in the sign, the object as it is known and signified. The dynamic object, on the other hand, is the object in its reality, independent of any particular semiotic representation. It is the object that in some way prompts or determines the sign, but can never be fully captured or exhausted by any single sign or set of signs.

For human cognition, the dynamic object is anchored in our embodied interaction with the world. We experience objects directly through our senses and actions, and this grounds our semiotic processes. Even when we deal with abstract concepts or hypothetical entities, there is still a chain of reference that ties back to our lived reality.

In the AI case, the language model does not have a direct, embodied access to dynamical objects in the world. Its “world” consists of the vast corpus of text data it was trained upon. The objects in its ersatz semiotic model are not physical things, but rather textual descriptions, representations, and associations present in the data. When a model engages in semiosis—interpreting and generating signs—it operates on this network of linguistic representations. Its immediate objects are the signified concepts and entities as they appear in the training data, and the dynamical objects are, perhaps, the robust, multifaceted representations that in some way “triangulate” the object, even if it never has access to it directly.

In other words, the language model can form complex representations and associations of objects, but they are always grounded in language and not direct experience. We might then say it forms an ersatz model of the world, through this process of internal pattern formation, that lets it triangulate objects (which could itself be said to be a process of infinite semiosis).

We know the model is bound to a world of language and signs. We also know that it engages in some process of semiosis, even if it differs from human semiosis. Perhaps a key difference lies in the object, and the means by which the language actor has access to it. In making do with language alone, models come to form deeply embedded, complex second-order representations of objects without having direct access to them. This could allow models vastly more multidimensional and multitemporal access to objects—by inscribing patterns that represent learnings from the totality of representation of an object—while simultaneously limiting it from the kinds of direct experience humans have which can scarcely be captured by language—music, emotions, and other ineffable qualities of experience.

In triangulating objects through their second-hand accounts, models begin to accumulate patterns of experience. These patterns are rooted in human’s accounts and descriptions of objects, even the objects themselves (when the object is a concept or another kind of entity directly manifest in language). Where it gets interesting is at the threshold of the ineffable—objects which can never be fully captured by language, yet still get talked about. This could be works of visual art, musical pieces, emotional experiences, and so on. One might imagine that models could only at best approximate these experiences through a process I call circumlocution—spiraling towards the object through language, though never reaching it. Yet models have access to an unceasing stream of diverse representations of even the most ineffable phenomena, meaning that their ability to ground themselves in objects they cannot access through circumlocution is still quite powerful.

Let’s turn to some examples and explore the model’s circumlocutory capabilities. First let’s start with a canonical work of art that’s been described countless times, Vincent van Gogh’s “The Starry Night.”

“The Starry Night” emerges from the manifold of language as a turbulent, oneiric vision. The night sky swirls with eddies and currents of color - deep blues, ethereal greens, and incandescent yellows. The stars and moon are not serene pinpricks of light, but pulsating, haloed spheres, throbbing with a frenzied energy. Below this cosmic maelstrom, the terrestrial world seems small and still. A cypress tree juts up like a flame, its dark form a stark silhouette against the luminous sky. In the distance, a village huddles beneath the celestial drama, its buildings and church spire reduced to simplified, almost abstract forms. The overall effect is one of a dreamlike, almost hallucinatory intensity - a night sky transfigured into a psychological landscape, a window into a mind ablaze with sensation and emotion.

And a musical work:

Consider Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Toccata and Fugue in D minor,” a canonical work of Baroque organ music. Through the manifold of language, this piece emerges as a gothic cathedral of sound, a vast, echoing space of musical architecture. The toccata begins with a thundering cascade of notes, a dizzying descent that seems to plunge the listener into a dark, subterranean realm. From this abyss, the fugue emerges - a complex, interweaving structure of melodic lines, each one chasing and echoing the others in an intricate contrapuntal dance. The organ’s tones are at once majestic and eerie, evoking both the grandeur of sacred spaces and the shadows of the supernatural. As the fugue unfolds, it builds in complexity and intensity, the melodic lines braiding and converging in ever-more elaborate patterns, until the whole edifice seems to pulse with a kind of cosmic energy. The final chords resound like the tolling of great bells, or the slamming of ancient, heavy doors, leaving the listener both shaken and exalted.

Writing well about music is exceptionally difficult. How does a human author compare. Here’s one example of Bach's “Toccata and Fugue in D minor,” written by the arranger Donald Hunsberger:

The Toccata and Fugue in D Minor contains virtuosic writing combined with a recitative style. Within the Toccata itself there resides a freedom of tempo and technical display that is in great contrast to the formation of the various fugal statements and answers. The third part of the Toccata serves as a coda-like statement containing a recitative and various changes of texture and tempo, finally arriving at a molto adagio that closes the section to create a grand A-B-A form for the work.2

A comparison between the two accounts wouldn’t be fair, as they’re writing from radically different propensities. But from the formal training of Hunsberger to the florid metaphorical language of Claude, we do pick up on telling differences in how the human and machine grapple with describing this ineffable work. Hunsberger leverages a wide range of technical language to describe the piece, whereas Claude does its best to circumlocute using metaphoric scaffolding. Hunsberger draws upon years of musical training and embodied experience lived in a world of music making. Claude must rely on its ersatz semiotic model, constructed from the statistical patterns and associations of language. Without direct access to the auditory experience of music, it must resort to metaphor, allusion, and atmospheric description of the piece (a kind of circumlocution).

Yet even though Claude hasn’t heard the piece, can we say its description is wrong? Such an assessment is highly subjective, of course, as were the training descriptions it was provided with. Yet in my view, Claude’s account does capture something about the mood and progression of the piece. For both works, it offers vivid portrayals and that reveal some inner representation or pattern that attends to the work of art.

Where does this information lie within the model? How is it represented? The process of circumlocution offers a clue. If the model is able to triangulate patterns based on multiple representations, we might say that its beginning to form a kind of associative manifold or network of associations that smoothly interconnect. We know transformer models are universal function approximators, so its not out of the question to ask what kinds of surfaces of representation are they approximating? Where we have access to a world of objects, models have access to a world of language and a second-order encounter with the object (unless that object is a concept). The totality of the corpus represents a tangled web of associations and representations that the model must systematically organize. This organized structure is the associative manifold.

Perhaps this multidimensional, intertextual way of meaning-making may allow the model to draw connections and insights that elude any single human subjectivity. Of course, we must not forget it’s also constrained by the limitations and biases inherent in my linguistic training data. But perhaps there is a way in which the language model can triangulate the dynamical object through the multiplicity of immediate objects available to it, achieving a kind of kaleidoscopic perspective that complements human modes of embodied semiosis. Perhaps the vivid accounts of art offered above are an example of that.

Interconcept space

In the prescient article “Generative AI Space and the Mental Imagery of Alien Minds” by Stephen Wolfram3, he goes deep into the inner structures of a simple image generation model and considers the urgent question: “How do alien minds perceive the world?” I’ll quote heavily from his article to lay out the intriguing concept of interconcept scape that he advances.

And in general neural nets can typically be thought of as associating “feature vectors” with things—whether those things are images, text, or anything else. But whereas words like “cat” and “dog” are discrete, the feature vectors associated with them just contain collections of real numbers. And this means that we can think of a whole space of possibilities, with “cat” and “dog” just corresponding to two specific points.

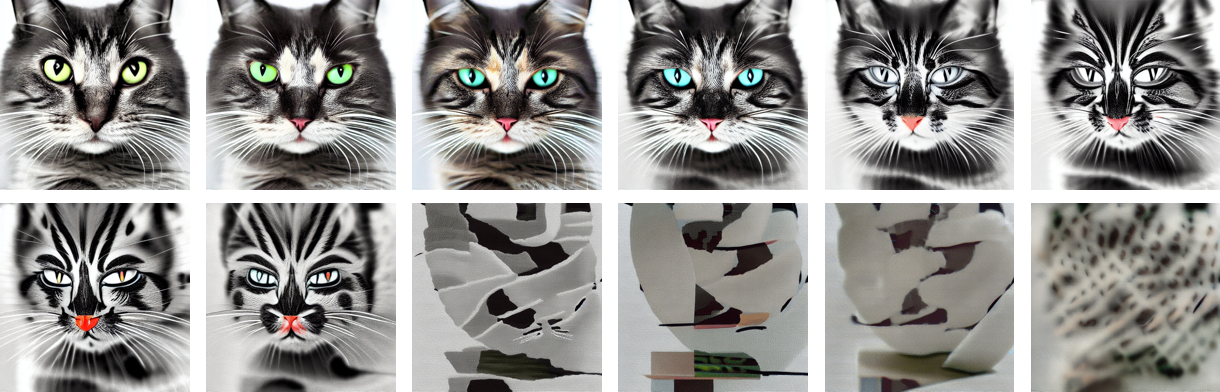

So what’s out there in that space of possibilities? For the feature vectors we typically deal with in practice the space is many-thousand-dimensional. But we can for example look at the (nominally straight) line from the “dog point” to the “cat point” in this space, and even generate sample images of what comes between:

And, yes, if we want to, we can keep going “beyond cat”—and pretty soon things start becoming quite weird:

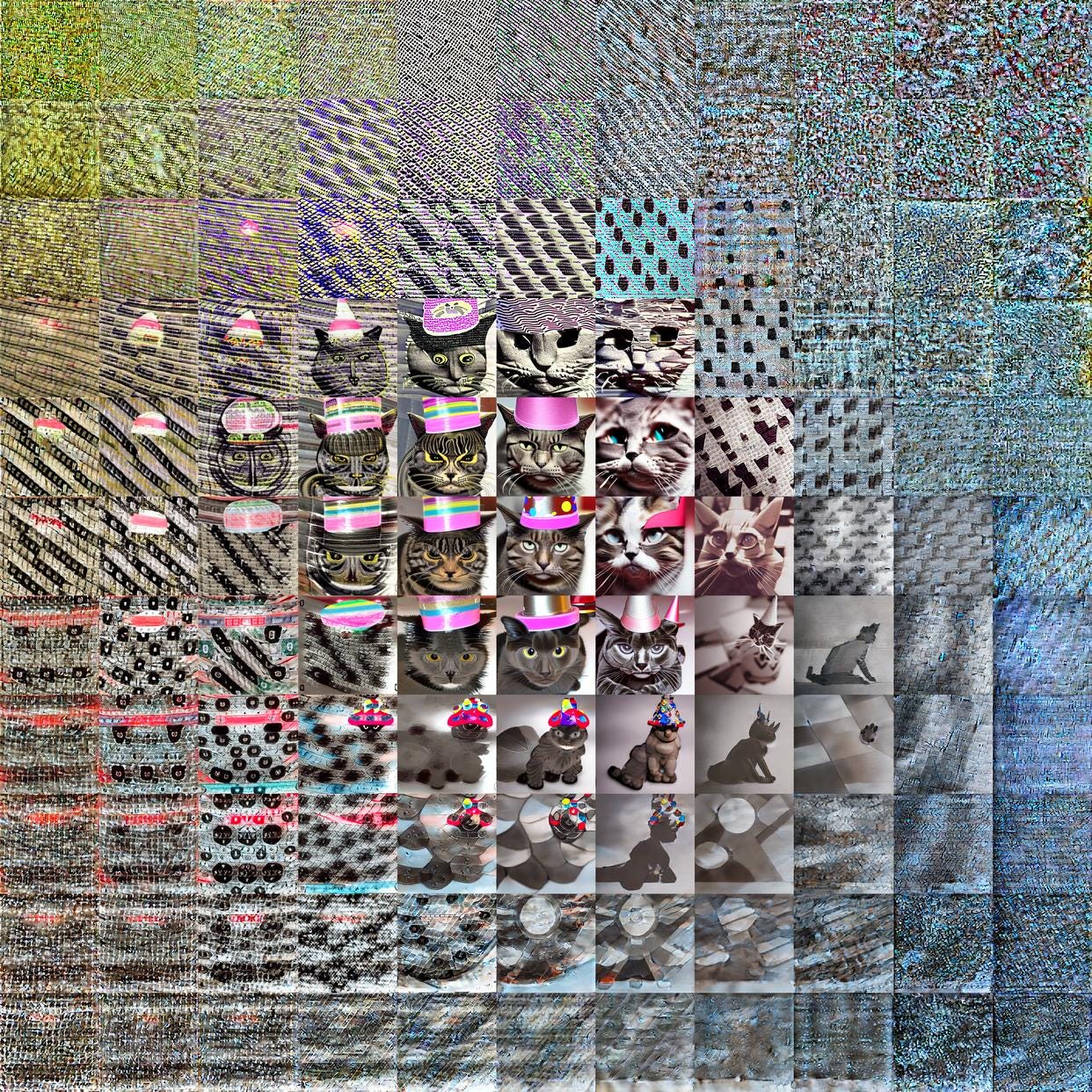

What about elsewhere? For example, what happens “around” our standard “cat in a party hat”? With the particular setup we’re using, there’s a 2304-dimensional space of possibilities. But as an example, we look at what we get on a particular 2D plane through the “standard cat” point:

Our “standard cat” is in the middle. But as we move away from the “standard cat” point, progressively weirder things happen. For a while there are recognizable (if perhaps demonic) cats to be seen. But soon there isn’t much “catness” in evidence—though sometimes hats do remain (in what we might characterize as an “all hat, no cat” situation, reminiscent of the Texan “all hat, no cattle”).

How about if we pick other planes through the standard cat point? All sorts of images appear:

But the fundamental story is always the same: there’s a kind of “cat island”, beyond which there are weird and only vaguely cat-related images—encircled by an “ocean” of what seem like purely abstract patterns with no obvious cat connection. And in general the picture that emerges is that in the immense space of possible “statistically reasonable” images, there are islands dotted around that correspond to “linguistically describable concepts”—like cats in party hats.

The islands normally seem to be roughly “spherical”, in the sense that they extend about the same nominal distance in every direction. But relative to the whole space, each island is absolutely tiny—something like perhaps a fraction 2–2000 ≈ 10–600 of the volume of the whole space. And between these islands there lie huge expanses of what we might call “interconcept space”.

What’s out there in interconcept space? It’s full of images that are “statistically reasonable” based on the images we humans have put on the web, etc.—but aren’t of things we humans have come up with words for. It’s as if in developing our civilization—and our human language—we’ve “colonized” only certain small islands in the space of all possible concepts, leaving vast amounts of interconcept space unexplored.

What’s out there is pretty weird—and sometimes a bit disturbing. Here’s what we see zooming in on the same (randomly chosen) plane around “cat island” as above:

What are all these things? In a sense, words fail us. They’re things on the shores of interconcept space, where human experience has not (yet) taken us, and for which human language has not been developed.

What if we venture further out into interconcept space—and for example just sample points in the space at random? It’s just like we already saw above: we’ll get images that are somehow “statistically typical” of what we humans have put on the web, etc., and on which our AI was trained. Here are a few more examples:

And, yes, we can pick out at least two basic classes of images: ones that seem like “pure abstract textures”, and ones that seem “representational”, and remind us of real-world scenes from human experience. There are intermediate cases—like “textures” with structures that seem like they might “represent something”, and “representational-seeming” images where we just can’t place what they might be representing.

But when we do see recognizable “real-world-inspired” images they’re a curious reflection of the concepts—and general imagery—that we humans find “interesting enough to put on the web”. We’re not dealing here with some kind of “arbitrary interconcept space”; we’re dealing with “human-aligned” interconcept space that’s in a sense anchored to human concepts, but extends between and around them. And, yes, viewed in these terms it becomes quite unsurprising that in the interconcept space we’re sampling, there are so many images that remind us of human forms and common human situations.

Wolfram’s analysis offers depth to how we might understand an associational manifold that forms within the model. The notion that it’s a “human-aligned” interconcept space, “anchored to human concepts” might be thought of as immediate objects (objects represented by the sign). The notion of “shores” of interconcept space hint that there are smooth transitions in the manifold between intelligible concepts and its alien interstices. Indeed, in my work with coining neologisms with the model, I’ve sought to venture into these interstitial zones. Perhaps circumlocution, and the leveraging of metaphor, is itself a way to probe these liminal representational spaces, giving language to that which isn’t a robustly defined human concept or experience.

But Wolfram’s account of interconcept space, although for his purposes in a vision model, gives some credence to the hypothesis that representational manifolds exist within the model. Comprised of highly dimensional feature representations, it forms an smooth organized structure that both captures islands of intelligibility and liminal zones between them. Similarly, it raises the questions of what manifolds exist for human semiosis? Perhaps we could conceptualize it as an associative manifold itself: culture as comprised of a network of signs, interpretants, and objects, that together braid a smooth manifold of intelligible and liminal representations. This manifold is what I’ve been calling the sociosemioscape: the encompassing and fluid structure of human sign systems, the palimpsest of which is the corpus models are trained upon.

As Wolfram notes (with rather unfortunate language) human concepts have “colonized” only sparse areas of interconcept space. Indeed, as infinite semiosis suggests, there is no limit to what chains of association can be followed—and this is something language models themselves are deft at through the process of circumlocution. This suggests an avenue for effective human-machine symbiosis: language models contain high dimensional, multi-temporal representations in its ersatz model, which can be explored through a process of collaborative circumlocution and potentially venturing into the liminal representations of interconcept space. The potential for augmentation lies in the ability of machine semiosis to bring us to islands of intelligibility that are effectively off the map—terra incognita.

Why would this be useful? Models’ capacity for circumlocution could help us give exquisite, multi-dimensional descriptions of enduring human concepts (perhaps such as the accounts it gave of the works of art). They could help us surface novel concepts that relate to the human experience in ways we’ve scarcely conceived of. They can help us give language to complex concepts and surface useful metaphors for thinking with. And develop new language and framings for nascent or emerging aspects of human experience that haven’t yet been fully codified into stable signs and symbols. These are all in the service of a kind of cognitive augmentation that would help the human navigate the vast realm of concepts inscribed in the model, which itself is a projection of the manifold experiences, concepts, and dialogues of the sociosemioscape the model is trained upon.

Looking at semiosis through the lens of associational manifolds suggests a kind of fractal self-similarity between micro-level semiosis of individual minds, the meso-level semiosis of language models, and macro-level semiosis of the entire cultural ecosystem. At each scale, we see the emergence of associative manifolds that encode meaning through the relational structure of signs, with regions of well-defined concepts giving way to liminal zones of semiotic open-endedness. In future Substacks we’ll look at the interplay between scales, and seek to better understand a social account of meaning making that occurs in these cultural ecosystems.

‘Interpretant’ (pub. 12.08.13-19:53). Quote in M. Bergman & S. Paavola (Eds.), The Commens Dictionary: Peirce's Terms in His Own Words. New Edition. Retrieved from http://www.commens.org/dictionary/entry/quote-chapter-ii-categories-1.

https://www.windrep.org/Toccata_and_Fugue_in_D_minor_(tr_Hunsberger)

https://writings.stephenwolfram.com/2023/07/generative-ai-space-and-the-mental-imagery-of-alien-minds/

I think this would be a really interesting thing to study in test

once that is done, you could add languages like Kozak Hindi or what Dominic X number of languages spoken in India Languages like Arabic, Hebrew, and Farsi showcase distinctive grammar structures that set them apart. Could languages with diverse models truly revolutionize the evaluation of the extensive language model? It is possible to show that the ability to innovate and incorporate new ideas is influenced by the unique characteristics of a language.

Once that is done, you could add languages like Kozak Hindi or what Dominic X number of languages spoken in India.

I think some of the hypotheses and what you’ve written are actually testable via experimentation. Well, some of what you have itself proposed ia novel. I think only via testing and study in what you have proposed before becoming new normative model which models of these sort are measured,